One of the first things I learnt in academia was the power of the systematic review.

It’s considered the gold standard of evidence based research, giving a summary of all literature on a research question. I did my first in 2016, when I had no idea what on earth a PICO was. I obsessed more than a little on the correct way to do a systematic review and so I decided to do this post- because 2016 me might have used it.

So what is a systematic review? LITERALLY a review done in a systematic way. It’s a method of such precise steps you probably obtain all existing papers on a topic you’re curious about. Using specific search terms and criteria to peruse databases, you locate the essential but weed out the unnecessary. Here’s an example of one I did on issues researchers face recruiting and including ethnic minorities in UK dementia research that I’ll be shamelessly plugging in as I go along.

So, how does it differ from a literature review?

Particularly relevant for postgraduate students, a systematic review can be your literature review. Because the extent of a literature review is undetermined you could do what is sometimes called a “dirty search”- searching Google or following up references in key papers. Often, through recent and reputable sources, that is enough to create a literature review. A systematic review is just a larger, more refined search process. It can be useful when a dirty search is coming up empty handed or you’re questioning whether you have enough evidence for your research question.

And what is a meta-analysis?

You may have heard this paired with a systematic review but what is it? It’s a follow up- a statistical cherry on the sundae if you want to not only have a summary of all the work in an area but also a mass analysis of all the data in that work to see if there’s a trend. All meta-analyses are systematic reviews but not all systematic reviews are meta-analyses.

What about qualitative research?

You can do a systematic review and overall qualitative analysis. That’s actually what I’ve done in my papers. You extract the data you want to analyze and simply conduct your analysis across all the papers. Even though this is technically also a mass analysis across papers and you may identify qualitative trends it wouldn’t be a meta-analysis. Only stats folks get that title. It would be labelled a qualitative analysis.

What is PRISMA though?

You’ll notice systematic reviews have a lot of acronyms. None is more important than PRISMA– Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Systematic reviews aren’t a garden variety literature search but a standardized method of steps to summarise a body of evidence. As with anything standardized there is often a set of guidelines to maintain those standards. For systematic reviews there is the PRISMA statement and checklist, which basically helps you conduct, structure and write up a systematic review to a certain quality. PRISMA is now your new best friend.

So how do you do a systematic review?

The three main steps that make a systematic review different from a traditional study are searching, screening and extraction.

SEARCHING

Search Terms

You don’t just type your research question as is. Instead, you identify key words or qualities each paper must have. In my case they had to be:

- About dementia

- UK based

- Including at least one ethnic minority group

Each of these is an inclusion criterion and if a paper did not include all three it was excluded. The intersection of these three bodies of literature is my review.

To get to this intersection I use search terms for each criteria .eg. when I search UK, I should also search United Kingdom, England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, in case people had used those instead of UK.

For ethnic minorities I should also search minority, ethnic group and multiethnic. Searching the names of individual ethnicities and terms for them would also enhance the search.

For dementia I should search subtypes like Alzheimer’s Disease. One trick is if I want to search dementia and also dementias I use an asterisk- dement*. This will give me all words with dement in them.

This is also where MESH can be helpful- Medical Subject Headings. These are pre-existing search terms for medical words that broaden your search. There’s a MESH browser you can use to track down these search terms.

You can also see if someone has done a review that covers one of your areas. An otherwise irrelevant paper on ethnic minorities may contain search terms for various ethnicities now at my disposal.

Search Strategy

Once you have all your search terms you must combine them. Related terms will be grouped by OR .eg. UK or United Kingdom or England.

Once you group all your related terms its time to create the intersection with AND .eg. “UK or United Kingdom or England” AND “dement* or Alzheimer’s*”.

You will also need to decide if you want to restrict your search to a certain time period of if you only want to look for the search terms in the titles of the papers instead of the full text. I usually restrict to the abstracts since titles can be too concise but full texts to plentiful.

What is PICO?

So I heard this a lot when learning about systematic reviews and it confused me because though helpful, PICO doesn’t always apply. It stands for the Population being studied, the Intervention used on them, the Comparator used versus the intervention, and the Outcome of the intervention on the population. This can help structure a research question and its search terms and identifying where the intersection lies. It works for trials, especially randomized control trials. But it’s not a one size fits all policy so don’t worry if PICO is not for you.

Databases

Time to use that search strategy to actually search something- databases. The ones in my field are ones like PubMed, MedLine, EMBASE, PSYCInfo but your library can often tell you which ones are relevant to you. These databases are giant repositories for journal articles. Some are more popular than others because more people search them, so more journals want to be linked with them and have their papers available through them. Not all databases have links to all journals, therefore, we search multiple.

We do this through a host platform, like OVID, which accesses multiple databases. All this means is that instead of typing my search strategy several times in each database, I can do it once on the host platform and get results from a myriad of them.

When you go on the host platform some have you type and enter each of your search terms individually and then we use OR and AND buttons to combine them as needed. You can also tick boxes for your restrictions.

Because you’re searching multiple databases, you may end up with several duplicates of a paper. A “Dedup” or “Remove duplicates” button will help to erase some of these.

In the end you’ll have a number- all the papers in that coveted intersection of yours.

If it’s too large?

Maybe your search has rendered 50k papers. Perhaps it’s a very popular topic. More likely, you need to go back to your search strategy and see if you’ve used specific enough terms, do you need more, have you used AND and OR correctly, and are your restrictions what they should be?

If it’s too small?

This often means a search strategy was too specific. But it can also be indicative of an under researched area which can make for a discussion point and be the whole basis of the systematic review.

If it’s just right?

If your search has produced a realistic number there should be an option to export the results. This could be as a PDF, spreadsheet or document. My personal preference is EndNote. The data that is exported will be dependent on the restrictions placed earlier; I usually get the year, authors, title, and abstract. It is this information you will go through and further eliminate stole aways that don’t meet the criteria set out.

SCREENING

PRISMA Flow Diagram

So PRISMA makes a comeback-as if it was ever really gone. A part of the systematic review process is keeping track of the number of papers found at each stage- from your search, after you’ve removed duplicates, and later on when you continue to screen papers out. These numbers go into a flow diagram, a blank version of which already exists thanks to PRISMA. The logic behind this is that if someone replicated your search they would get the same numbers and end up with what you did.

Screening Process

Screening is shrinking down the number of papers you have. First you’ll go through the titles, then abstracts, and finally full texts. Remember that full texts can be accessed in a variety of ways and all avenues should be explored to make sure they meet the criteria set out. Sometimes unrelated papers sneak in, sometimes they partially meet the criteria .eg. UK based dementia research that does not include ethnic minorities. This process of elimination also gives you the chance to find more duplicates.

Screening of all papers should be done individually by more than one person, because it makes the final number of papers you settle on that much more reliable. You can also have a mediator, a third individual, who helps decide whether a paper is included or not when the screeners disagree.

What is a protocol?

A protocol is actually a precursor to a systematic review. But there’s a reason I bring it up now. It is a basic blueprint of what your systematic review sets out to do and will detail all the methods stated so far. The protocol can be written up and even published as long as data extraction hasn’t been conducted.

EXTRACTION

Extraction Sheets

Now that you have a final list of papers that are all about your research question it’s time to milk them for what they’re worth. You start by developing a data extraction sheet.

This is done “a priori” which is just beforehand, and usually on a spreadsheet. There are standard things your review should tell a reader and you should therefore extract; year of publication, aim, methods, country, and sometimes language.

Then there will be specific data pertaining to your research question. For quantitative systematic reviews, and any subsequent meta-analyses, this will be stats reported in the results of the paper. For my review, in which I needed to find issues researchers faced, I mostly searched methods and discussion sections. Instead of numbers, I was extracting blocks of text.

Not all papers will render data but they remain in your review as long as they meet that initial criteria set out. Their lack of data can in and of itself be a trend in the research.

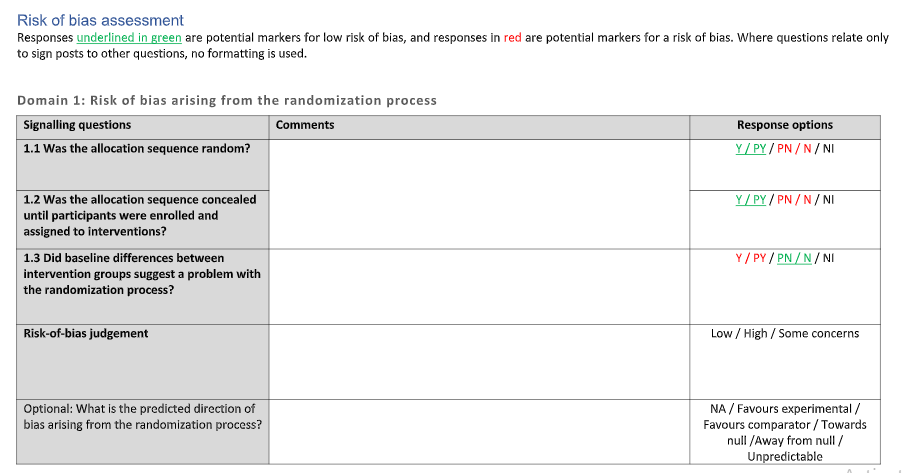

What is Risk of Bias?

ROB, or Risk of Bias, is something PRISMA asks for- the gift that keeps on giving. Often, when papers are included in a systematic review, their quality is assessed since not all published research is necessarily reliable or valid work. Different assessments of quality exist that different kinds of papers can be assessed with.

A specific type of assessment is to see what the risk of bias occurring in a study was and it’s just another questionnaire that needs to be filled for each paper. A popular one is the Cochrane RoB tool.

Discussion Section .aka. Final Thoughts

So that is the gist of the systematic review and how to do it! In all honestly, doing it once makes it so much easier to repeat. And following others’ systematic reviews provides templates and guidance for conducting and writing up your own. 2016 me would be really relieved to find out she can now do systematic reviews left, right, and centre and hopefully, now you can too.

A month ago a

A month ago a